Mechanical Ventilation

(Clark, 2017; Howard, et al., 2003; Respiratory Therapy Zone., 2021; Zanni, n.d.)

85-90% of patients in the ICU require mechanical ventilation (MV). Most patients wean easily once the reason for MV is resolved. However, 20-30% need more time to wean. Reintubation is associated with 30-40% increase in mortality.

A patient can be connected to the ventilator in 1 of 3 ways:

Nasotracheal intubation (nose) – Short term

Endotracheal intubation [ETT] (mouth) – most common; short term

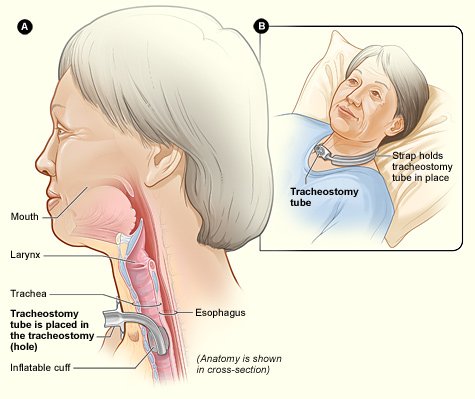

Tracheostomy (throat) – for extended vent weaning; long term

Translaryngeal tubes (ETT or nasotracheal) are measured to a specific depth. Tubing has hash marks with numbers to indicate the distance until the end of the tubing. *Tubing should not go into/out of the mouth/throat further. Take note of the position of the tubing and measurement at the lips or nostrils. Monitor before/during/after transfers.

A cuff is inflated around the tube to ensure that the air is being delivered directly into the lungs. If a cuff leak is suspected, the patient may be able to phonate or make audible sounds from the mouth. Alert RN immediately.

Endotracheal Intubation (ETT)

Tracheostomy

For Further Explanation

*Vent tube disconnection is common and very different than extubation*

Should the patient accidentally become extubated:

Prepare: be familiar with the ambu bag’s location in the room and have a plan of action in mind

Prevent: do not underestimate the patient’s determination to self-extubate. Keep your eyes on the patient at all times and be prepared that they might try to pull out the tubing.

Follow a plan: 1) Call for the RN and place the patient in a safe position; 2) while maintaining the patient’s physical safety retrieve the ambu bag, 3) begin providing respiration and attach the ambu bag to oxygen

(Clark, 2017)

Common Reasons for Intubation in the Neurology ICU

(Howard et al., 2003)

Generally required for airway management with intubation indicated for patients with:

Impaired level of consciousness (GCS <9)

Progressive respiratory impairment/failure

Inability to oxygenate (due to high secretions) or ventilate (i.e., myasthenia gravis)

Impaired cough or airway clearance

Pulmonary edema/aspiration

Seizure activity

Terms and Norms

Tidal Volume (VT): amount of air inhaled or exhaled with each breath (based on weight).

Average healthy male adult: 500 ml.

Positive End Expiratory Pressure (PEEP): pressure applied by the vent at the end of each breath. Varies can be increased or decreased as needed. There is a constant amount of baseline positive airway pressure (i.e. 5 cm H20) that’s maintained even at end of expiration. Assists in keeping alveoli open to minimize atelectasis.

3-5 cm H2O (low): physiologic; used to preserve normal functional residual capacity (FRC=expiratory receiver volume + residual volume)

5-15 cm H2O: used to treat refractory hypoxemia in acute lung injury

>15 cm H2O (high): used only for severe lung injury (likely candidates for proning or ECMO). Mobility not indicated.

Pressure Support (PS) norms: 0 cmH2O to 30 cmH2O. Usually 5-15 cmH2O.

≤ 5 cmH20 LOW vent settings; may be ready to extubate.

≥ 20 cmH20 HIGH vent settings; Not stable/likely not ready for mobility.

FiO2 (fraction of inspired oxygen): concentration of oxygen in the gas mixture.

“Room air” is 21% FiO2 (or 0.21). Usually see 30-60% (0.3-0.6) for a patient requiring vent support.

Vent can provide up to 100% FiO2. Patient who requires high FiO2 support likely unstable/not appropriate for therapy; If Patient decompensates, additional support is limited.

Ventilator Modes & Settings

Determined by the MD and RT. Settings will vary depending on the patient’s needs.

Control mode is the most dependent

Patients generally progress from more dependent to less dependent modes prior to extubation. You might see a progression from sustained intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) to pressure support volume (PSV) and to continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) prior to the ability to be extubated.

Note. Adapted from “Intensive Care Unit”, by K. Clark, 2017, table 9.6, p. 120, in Occupational Therapy in Acute Care, AOTA Press. Copyright 2017 by AOTA Press. Reprinted with permission.

Most Common Ventilator Modes

-

Assist-Control (A/C) (Respiratory Therapy Zone, 2021)

Non-weaning mode. Pre-set: Rate & Vt

Minimum number of pre-set mandatory breaths are delivered by the vent, Patient CAN trigger assisted breaths. However, the vent will deliver pre-set Vt when this happens. Doesn’t allow for spontaneous breaths.

Can be volume (more common) or pressure-assist control.

On Hamilton G-5 vent mode will read: (S)CMV for volume A/C or P-CMV for pressure A/C

Parameters that should be noted ON the ventilator: Confirm: mode, rate, target variable (volume OR pressure control), FiO2, PEEP

-

Synchronized Intermittent Mandatory Ventilation (SIMV) (Respiratory Therapy Zone, 2021)

Weaning mode. Pre-Set: Rate & Vt

Vent delivers a pre-set minimum number of mandatory breaths. Patient CAN breathe spontaneously between vent breaths.

Each spontaneous breath receives a Vt dependent on the Patient’s effort NOT the pre-set Vt. **Often used with PSV to help overcome the resistance of vent tubing on spontaneous breaths.

On Hamilton G-5 vent mode will read: SIMV

Parameters that should be noted ON the ventilator: Confirm: mode, rate, target variable (Volume OR Pressure control), FiO2, PEEP, Pressure support

-

Pressure Support Ventilation (PSV) (Respiratory Therapy Zone, 2021)

Spontaneous breaths supported by the vent during inspiratory phase of breathing. When Patient triggers a breath, vent assists by adding pressure to make breathing easier. May be applied to spontaneous breathing during SIMV or CPAP.

Once the patient triggers the vent: Pre-set positive pressure is delivered. Volume is NOT pre-set. PS augments Vt.

Patient in control of RR & inspiratory time.

No guaranteed ventilation or RR. (Except back up apnea rate).

On Hamilton G-5 vent mode will read: SPONT

Parameters that should be noted ON the ventilator: Confirm: mode, PS, FiO2, and PEEP

Common Medications while Mechanically Ventilated

Further Reading

Miller, N. (2013). Set the stage for ventilator settings. Nursing Made Incredibly Easy, 11(3), 44–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NME.0000428429.60123.f7

Zanni, J. (n.d.). Understanding Mechanical Ventilation. https://www.johnshopkinssolutions.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/4-Understanding-Mechanical-Ventilation.pdf

References

Clark, K. (2017). Intensive Care Unit. In H. Smith-Gabai & S. E. Holm (Eds.), Occupational Therapy in Acute Care (2nd ed., pp. 115–135). AOTA Press.

Howard, R. S., Kullmann, D. M., & Hirsch, N. P. (2003). Admission to neurological intensive care: Who, when, and why? Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 74(suppl 3), iii2–iii9. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.74.suppl_3.iii2

Respiratory Therapy Zone. (2021). Ventilator modes made easy (study guide for mechanical ventilation). Respiratory Therapy Zone. www.respiratorytherapyzone.com/ventilator-modes-practice-questions/

Zanni, J. (n.d.). Understanding Mechanical Ventilation. https://www.johnshopkinssolutions.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/4-Understanding-Mechanical-Ventilation.pdf